And then there is Granada.

If anyone were to ask my advice about visiting Granada, I would say “Spend twice as long as you are planning. It still won’t be enough.”

The main feature for tourism in Granada is the Alhambra, and that was why we went. I had no idea I would become so totally enchanted by the city and the culture. We had a magical room in a guest house, Solar Montes Claros, in a neighbourhood on hill above the city centre, the Albaicín. If we had done nothing else, the trip would have been worth it just to spend time there. Spacious and designed like something out of the Arabian nights, it overlooked the Alhambra and the city below with stunning sunsets.

After a day of hiking in the hills, It was glorious to soak my aching muscles in a bath fit for a queen.

The Albaicín is the oldest Arab district in Granada. The roads are a maze of narrow streets and the hills are steep –– perhaps not the ideal location for aged hips. But I’m so glad to have discovered it. It had a huge influence on our experience in Granada. We only just scratched the surface of what is there.

On our first afternoon, we navigated the streets up to the best look out point, the Mirador San Nicolás. I’m embarrassed to say that I had done very little research about Granada before we left –– if I had, I would have found out that this small square is considered the best view in Granada. It is phenomenal and somewhat life-changing. The sun shone and a handful of people gathered in the small plaza to soak it in.

We spent a small fortune to sit at a restaurant and have wine, immersed in this beauty on the edge of the rock, with the Alhambra and the snow-covered Sierra Nevada mountains in the distance. It was worth every penny.

Albaicín is adjacent to Sacromonte, which is the neighbourhood that the Roma moved into in the 15th century. Both Albaicín and Sacromonte are known for the white-washed caves (cuevas) that were carved out of the rock for people to live in. The area is still a stronghold of Roma culture. Importantly, it is the home for flamenco in Granada.

The caves are small, and those that are used for flamenco have a few chairs and tables and a small stage. If they are really small, they may only have a few chairs tucked along the sides of the cave. You can often buy dinner as well. A drink is always included.

I found a cave called El Templo del Flamenco that sounded like it would not be too touristy, so I purchased tickets for that evening. We set off with our GPS lit up. It is very easy to get lost in the maze of roads. Sharp turns and steep cobbled inclines transformed into drastic plunges only to spike upwards again. I kept my eye on the GPS, but it turns out that while GPS is fine on flat landscapes, it struggles to differentiate levels. In other words, we would follow it to where it told us to go, only to find out that our true destination was on the street directly above us. Which would mean retracing our steps and re-negotiating the hills we had just been on. At one such juncture Tim was ready to bail. “How much did you pay for these tickets…?” But we persevered and finally found our way to El Templo del Flamenco and a cave that holds about 40 people.

I don’t have any critical eye to describe Flamenco. I know that this show was very good, but it didn’t thrill us as much as the raw energy we had felt in Cordoba. But that may have been entirely subjective. However, this was the only place we saw a male dancer and he was astonishing. Somehow he conveyed humour and passion in such a way that we thought he might explode on the stage. I thought back to the definition of Duende: A heightened state of emotion, expression, and authenticity. A tragedy-inspired ecstasy. He embodied all of that. I don’t know how his body contained that energy. Try to imagine Buster Keaton, Fred Astaire, Rudolf Nureyev, Michael Jackson and Leonard Cohen all wrapped up together. He was that good.

We were a bit dazed as we wound our way back to the guest house. We found a square where we stopped for a light dinner at a Taberna –– the owner told Tim what he wanted to eat and would brook no argument. But we were happy to eat whatever he brought (as it turns out, he brought a hot stone sizzling with some pork medallions on it), as we sat outside under a soft drizzle of rain, our ears and eyes filled with magic and questions.

The next day was our day to go to the Alhambra. In the morning, we walked down (and down and down) into the city and were stunned when we got there to see how cosmopolitan it was. In front of the Cathedral we came across a red carpet and what was obviously a paparazzzi moment. We learned that the Goya Awards (Spain’s equivalent of the Oscars) were being held in Granada that night. That gave the city an additional sparkle of glamour for us.

The centre of town has thoroughfares of dense traffic on spacious wide streets but leading off these are surprising narrow alleys that open out to plazas that feel like small villages. We found a children’s carousel made of wooden animals and powered by a man pedalling a stationary bicycle. An “eco-carousel.”

We had coffee and absorbed a bit of city life until it was time to head up to the rarified atmosphere of the Alhambra.

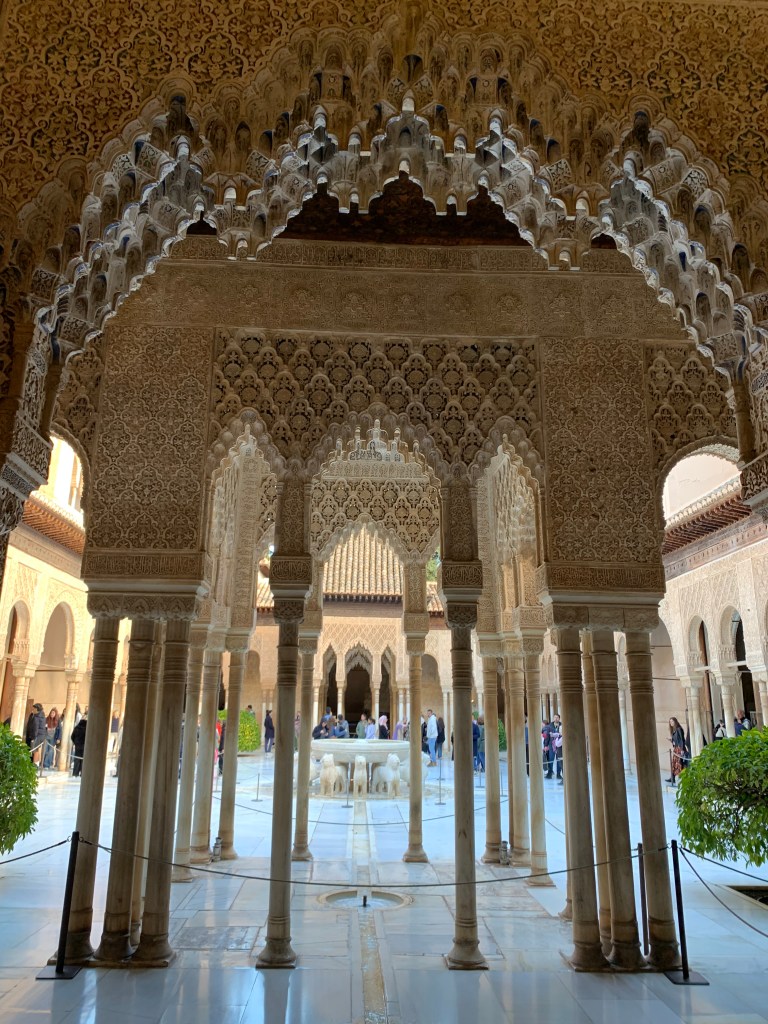

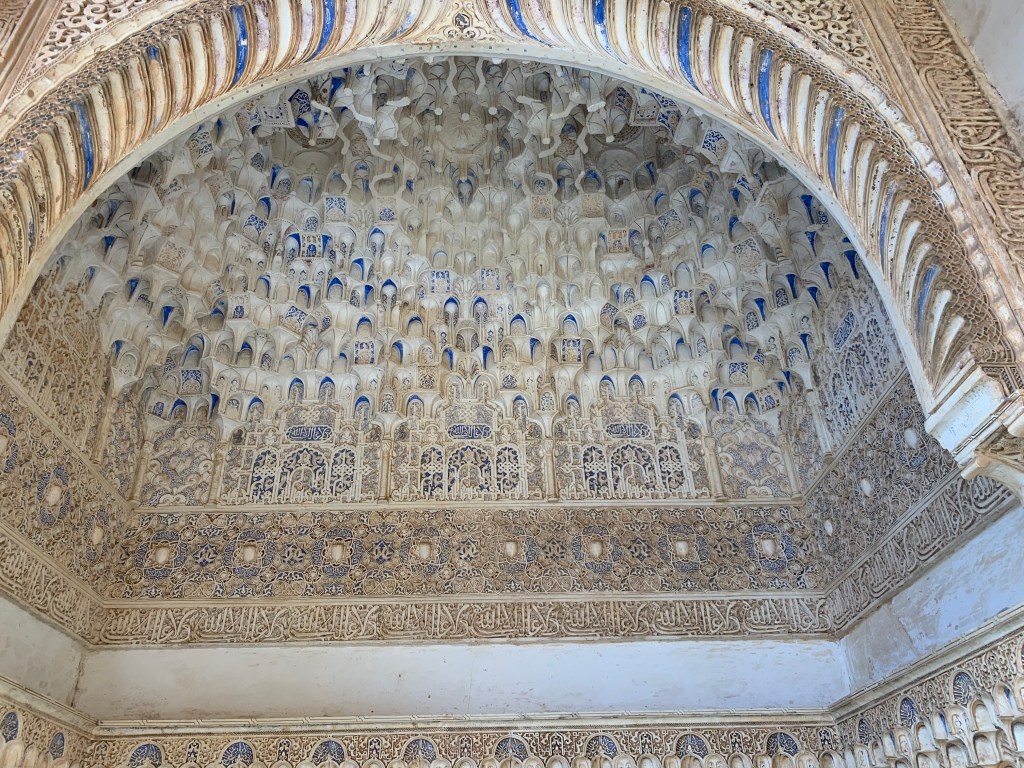

The Alhambra is one of the best-preserved palaces of Islamic architecture. The site atop the al-Sabina hill in the Sierra Nevada mountains commands the surrounding countryside. Constructed in 1238 by Muhammad I Ibn al-Ahmar (the first Nasrid Emir and founder of the Emirate of Granada) over pre-existing Visigoth and Arab fortresses, the Alhambra was to be the last holdout of the Al-Andalus empire. In its hey-day, it was a self-contained city that looked out to the town below.

The Emirate of Granada fell to the Spanish Reconquesta in 1492. The Arab palace became the court of Ferdinand and Isabella. Christopher Columbus presented his sailing plans here, in the Hall of the Ambassadors. Today, it is a UNESCO World Heritage site that is astonishing for its location, gardens, complex tile and carvings.

It is hard to grasp the beauty and detail in these tiled walls, arches, and fountains. Around every turn there is a window framing a courtyard or the vista of the landscape.

It would take many days to truly do justice to the grandeur of the Alhambra. The carvings, the gardens, the reflecting pools –– it is hard not to be overwhelmed by this beauty. It has inspired writers throughout the centuries, including Washington Irving whose Tales of the Alhambra (1832) brought the palace to international attention.

We spent two hours just walking in the gardens (Generalife) and even though it was February, when the plants in the gardens were dormant, we were overwhelmed by the grandeur.

The Alhambra was definitely the pinnacle of our journey into the Islamic architecture of Al-Andalus.

But Granada is far more than the Alhambra. At the bottom of the street where we were staying in Albaicín was another flamenco cave, La Cueva Flamenca Los Parrones. We had been approached on the street by one of the owners (we think he was – my Spanish isn’t great) who persuaded us to come to the show. We said we would since it was going to be the last chance we’d have to see more flamenco on this trip. But could they give us something to eat that night if we came? We were taken to the kitchen to smell the stew they would give us, an Adalucian specialty with chick peas, vegetables, and meats called Puchero. “Como tu abuela hacia!” (Like your grandmother used to make!) It smelled heavenly. We were sold. And so, after a post Alhambra rest, we went out for our last night of Flamenco.

We sat with fourteen other people in a tiny room carved out of the rock.

We were given pride of place right beside the performers, literally so close that the dancer accidentally kicked Tim at one point. The guitar player needed to turn sideways so as not to hit me when he needed to tune. It’s not hyperbole to say we were transported by the music and energy of this moment. This was our experience of duende, although without the stripping of clothes or throwing chairs.

After the show we were taken into a side room and fed salad and soup and more wine. We were the only people eating — it clearly wasn’t something they were usually set up to do but they treated us royally. It turned out that this was only their fourth night of operation and everyone was partying in the other room. We were hugged by the guitar player, by the man who made our amazingly delicious stew, and by the man who had persuaded us to come (who you can see in the photo.) We were made honourary abuelos, grandparents, and I couldn’t be more honoured.

I left a piece of my heart there.