I’m pinching myself.

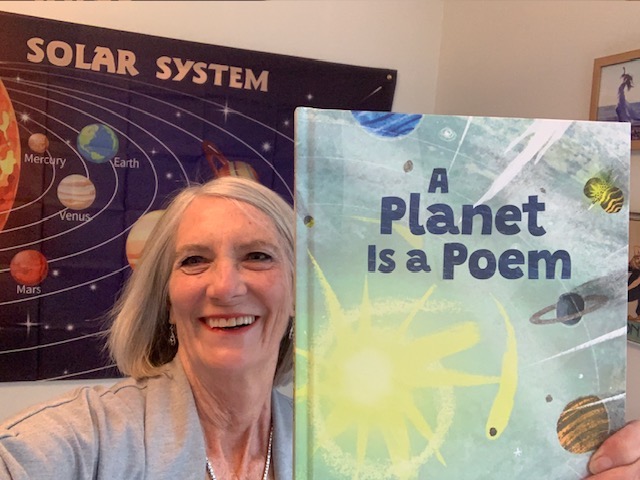

Last night, my book A Planet is a Poem was honoured with the Lane Anderson Award for science writing in Canada, youth category. So much of the credit goes to my editor, Kathleen Keenan, at Kids Can Press. She is a visionary!

The book combines an exploration of the Solar System with an exploration of poetic forms. For me, science and poetry are a natural pairing — they are both ways of trying to understand the world through metaphor and imagery.

I am deeply grateful to the committee and to the Fitzhenry Foundation for their support and encouragement. I sincerely congratulate my fellow nominees, Monique Polak, Remember This: The Fascinating World of Memory, and Rachel Poliquin, I am Wind: An autobiography.

Before we were presented with the results, each nominee was asked to say something about their book. Here is what I said:

First of all, let me say how incredibly honoured I am that A Planet is a Poem has been shortlisted for the Lane Anderson Award. To be recognized for science writing is humbling –– especially as I am not a scientist. I’ve spent my life in the arts. But I think that artists and scientists have, at base, a common, shared desire to make sense of the world. We may have different approaches, but our need to express our curiosity comes from the same root.

It’s thrilling when a passionate scientist makes sense of their area of expertise for a lay person. You hear that passion every week on the CBC radio show Quirks and Quarks. (I’m a big fan.) In each episode, you hear passionate scientists sharing their latest discoveries –– a beetle, a volcano, the discovered moons of Saturn.

But many of the things that scientists need to explain are huge concepts beyond our understanding. To bring their knowledge to non-scientists, they must find language that describes the indescribable. Inevitably, they resort to metaphor and imagery. And in doing that, scientists and artists share a common language. Poetry.

In 2015, Quirks and Quarks featured a number of reports from the New Horizons Space Probe. The probe had just sent back the first “close ups” from Pluto. The scientists could barely contain their excitement. They talked about Pluto having a red, heart-shaped plateau on it that ebbs and flows. Just like a beating heart, they said. What an image! A beating heart on the edge of our solar system! Who couldn’t fall in love with that? Then someone on the program said: “The skies above Pluto appear as bright blue.” Blue skies? Blue skies on the edge of the solar system? I quoted that line to everyone I knew. “The skies above Pluto appear as bright blue.” “Did you know: The skies above Pluto appear as bright blue?”

At the time, I was in the midst of studying into different poetry forms. I heard rhythm in everything. “The skies above Pluto appear as bright blue” is iambic tetrameter.

As an exercise, I decided to use that rhythm and make a Pantoum for Pluto. A Pantoum is a complex poetic form, like a puzzle. I’d never written one, and I liked the alliteration of “A Pantoum for Pluto”. Suddenly I was deep in imagery, metaphor, rhythm, rhyme and exciting new science. I dug deeper. I was doing exactly what scientists need to do –– explain things through image and metaphor to excite and spark people’s imagination.

I became hooked on poetry and planets. I was lucky enough to connect with my editor Kathleen Keenan at Kids Can Press. She, too, is mad about poetry and planets. Since I was deeply into studying different poetic forms, Kathleen suggested I try writing about each planet in a different form.

So I set to work researching the planets. As I researched, I realized that they had wildly different characteristics. I’m primarily a novel writer and a theatre person, and when you write a novel or a play you get to know your characters intimately. You learn their rhythms, their pace, their idiosyncrasies, their likes and dislikes. The planets presented themselves to me in the same way –– as characters in the great play of the Solar System. I realized wanted to support their uniqueness by pairing them with different poetic forms. Thus, Mercury, who spins very quickly, is contained in a fast-paced poem with rhythms that echo Dr. Seuss. “Mercury’s tiny/ Of planets the smallest/ But named for a god/who was known as the fastest.” There is, incidentally, a crater on Mercury called Dr. Seuss. Uranus, who spins sideways like a barrel and has a huge corkscrew-like magnetic tail that stretches for millions of miles, is written in free verse that echoes its unique, “free spirit” nature. And Pluto? Pluto is not a Pantoum – however much I loved the alliteration of A Pantoum for Pluto. No, Pluto is in a Companion poem with Charon, the two of them permanently linked and inseparable. Two poems that twine together.

The book became an interconnected way for young people to learn about our Solar System and about poetry.

When I was a little girl, I went to the Hayden Planetarium in New York. I had no knowledge of the night sky, other than the occasional glimpse of the moon. I was a city girl, and visions of stars, let alone planets, were not easy to come by. But that trip to the planetarium, with its mechanical whirling planets, sparked my little girl imagination. Writing this book was my gift to that child, and to all children, especially those who are not scientifically minded, those who live in cities and can’t see the stars, but are young people whose scientific imaginations can be sparked though the arts and go on to have a greater understanding of the world around them.

Thank you very much.